IMPACT OF COVID-19 CAUSES CONCERN FOR PROGRESS OF MOUNT EVEREST BIOGAS PROJECT

Following recent profiles on the progress made by two past UIAA Mountain Protection Award winners – Mountain Wilderness France (2016) and AlpineLearning Project Weeks (2019) – the focus turns to 2017 winner Mount Everest Biogas Project (MEBP).

The United States-based project, launched in 2010, is a volunteer-run, non-profit organisation that has designed an environmentally sustainable solution to dealing with the impact of human waste on Mount Everest and eventually other high altitude locations. This year was set to witness significant on-site progress on Everest but the Covid-19 pandemic, as detailed below, has caused significant hold-ups.

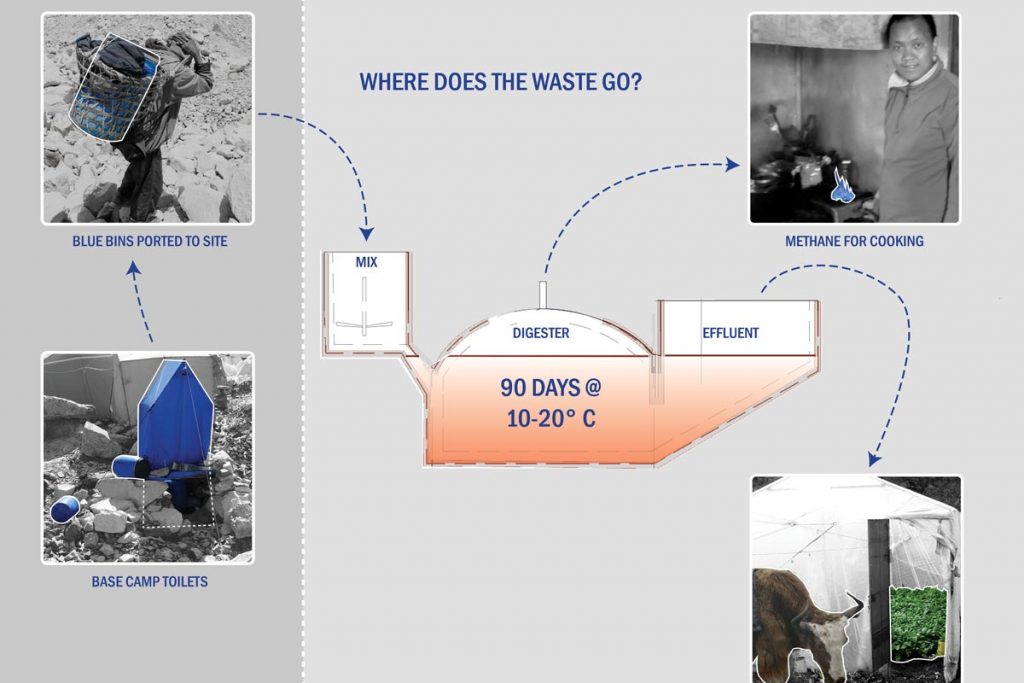

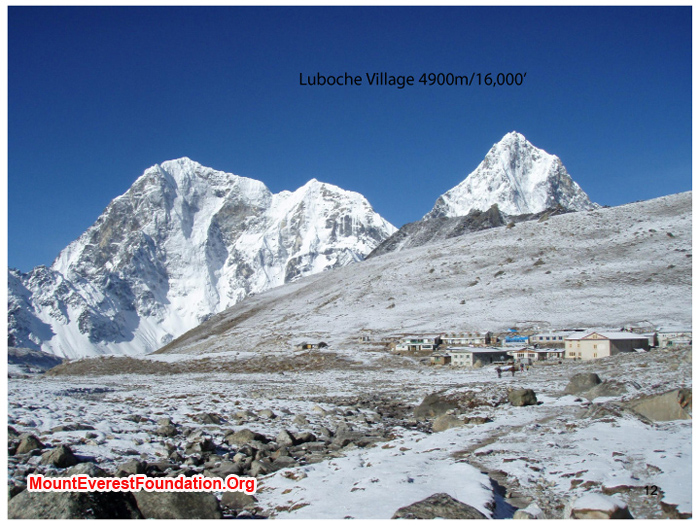

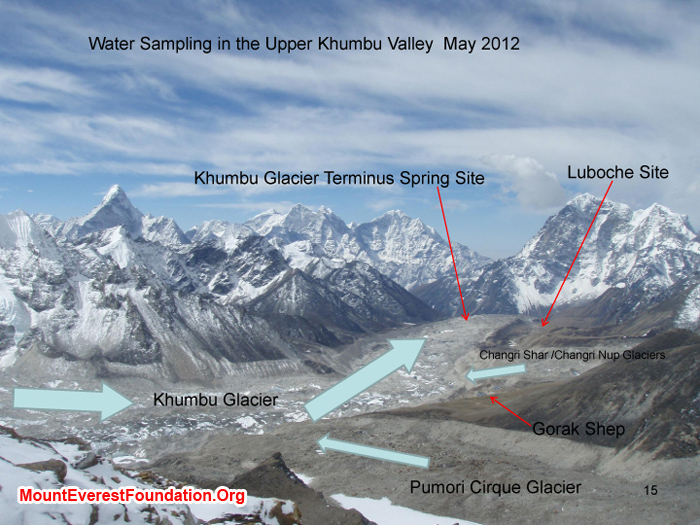

Mount Everest boasts a massive climbing industry, with hundreds of climbers – and support staff – make the trip up the Khumbu Valley each year (2020 being an obvious exception). This tourism has left a trail of human waste, approximately 12,000kg per year, that has given way to environmental and public health concerns. MEBP’s proposal is to use an anaerobic biogas digester to treat human waste. It will eliminate the dumping of solid human waste and destroy pathogenic fecal coliforms that threaten the health of the local communities – lessening the impact of the tourism industry on a mountain that is sacred to the Nepalese.

The Mt. Everest Biogas Project was designed to address this environmental and health hazards in a sustainable manner and serve as a model for other regions that must deal with similar waste problems at high-altitude, regardless if it is caused by climbers or local communities. The system will convert waste into methane, a renewable natural gas, and a reduced pathogen effluent.

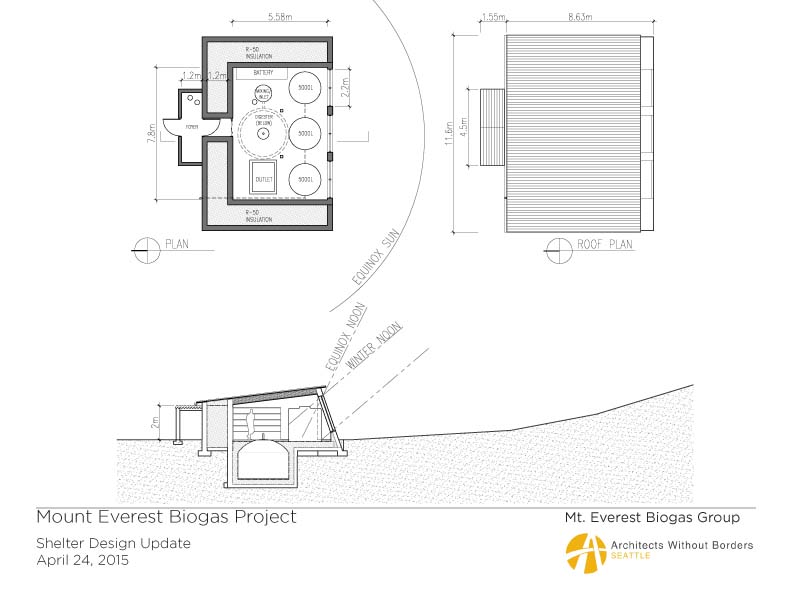

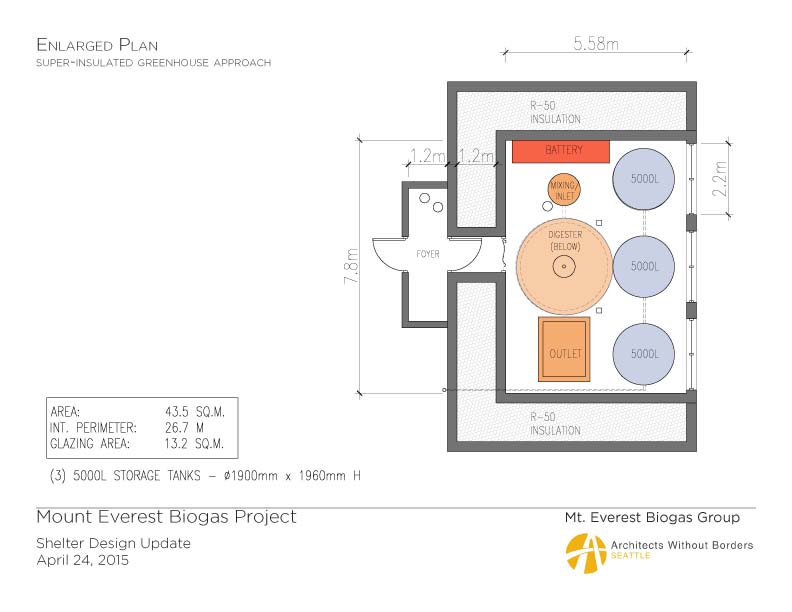

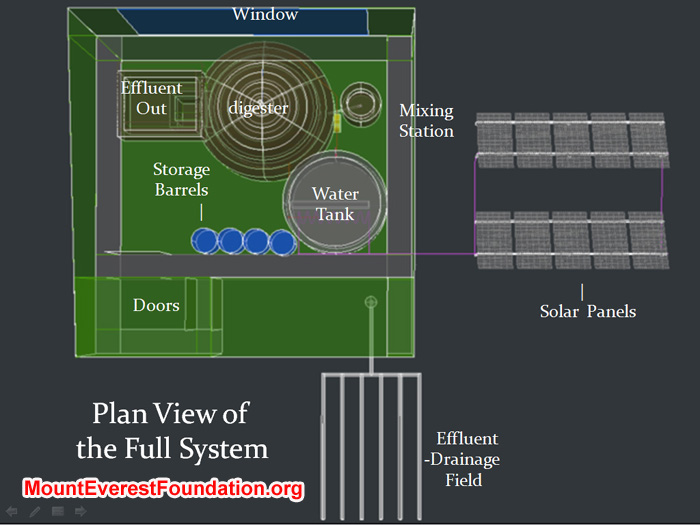

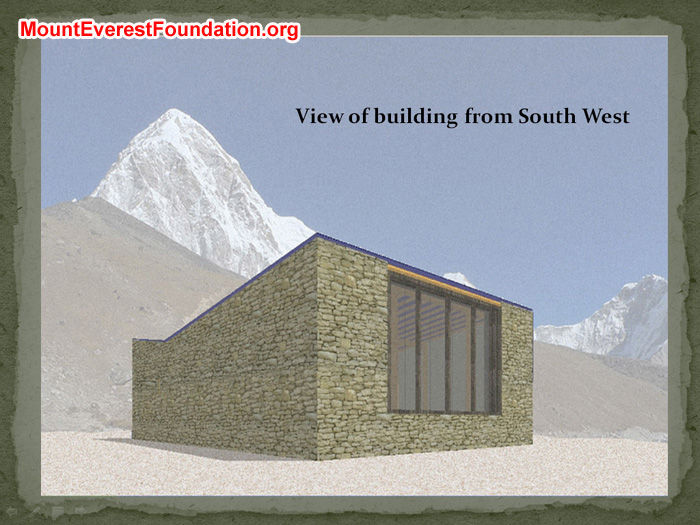

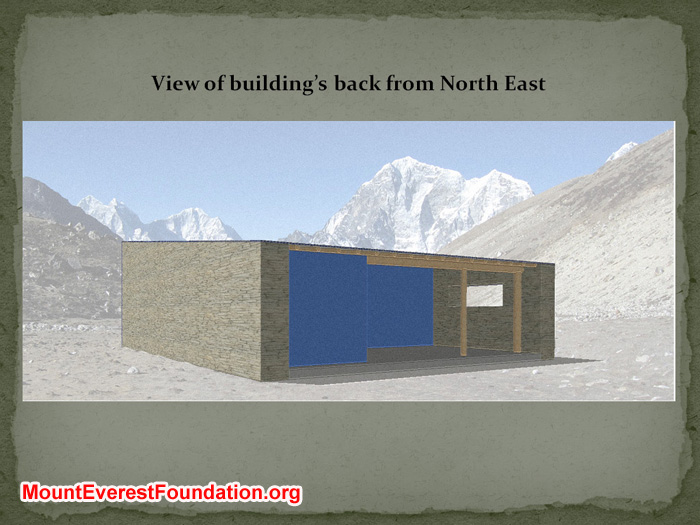

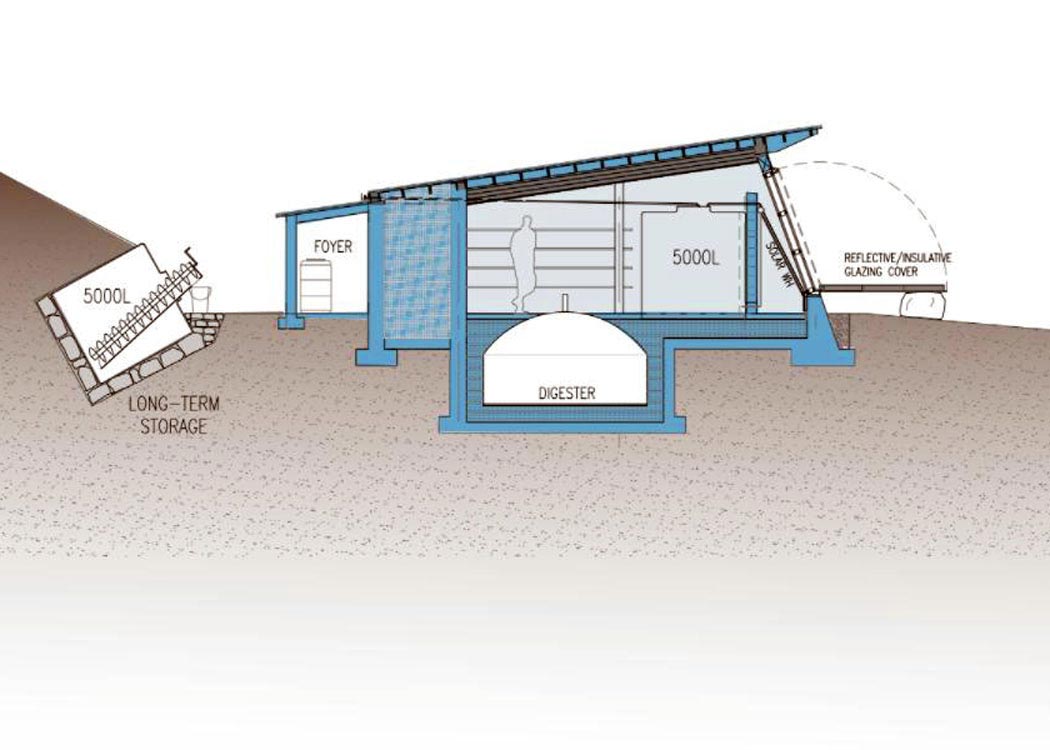

Mount Everest Biogas Project – Site render

Following the project’s MPA win in October 2017, groundbreaking for the biogas digester was planned for spring 2018 and an operational date slated for winter 2019, early 2020. The UIAA caught up with Dr Daniel Mazur, head of the project, to assess progress made during the past few years and in particular the impact of Covid-19.

UIAA: How much of a boost to the Mount Everest Biogas Project was winning the 2017 Mountain Protection Award?

MEBP: The Award brought recognition from an established international organisation, providing the MEBP with much welcome exposure as a legitimate development project for all those familiar with the UIAA. This has broadened our project’s recognition, and encouraged donor’s trust.

Can you briefly summarise how the project has evolved since 2017?

In 2018 we fully vetted our design, travelling to Nepal and signing Statements Of Work (SOW) with all the Nepali subcontractors we will work with to build the system. These SOW detail the scope of work for the subcontractors to accomplish and the cost expected at that time. So at this time we have all the required Nepali subcontractors lined up to start construction, and we have approval by the local government authorities to build within the Mt. Everest National Park. We have been working with Kathmandu University on a biogas research component for proof of design.

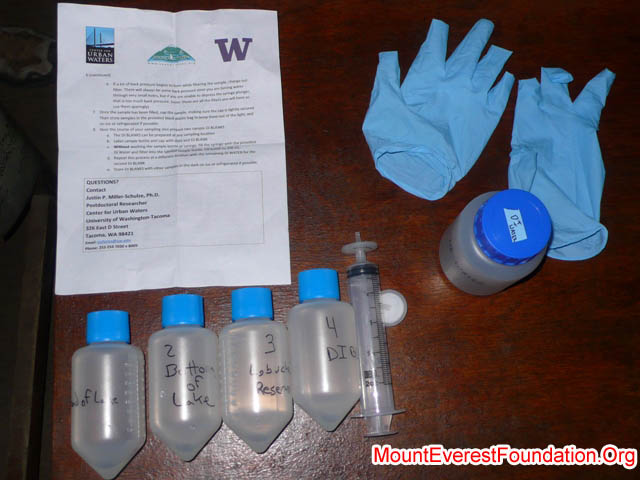

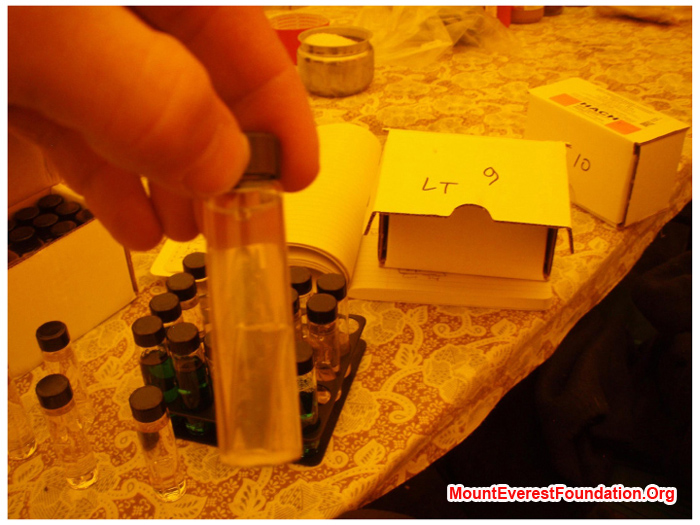

What sort of testing has been taking place?

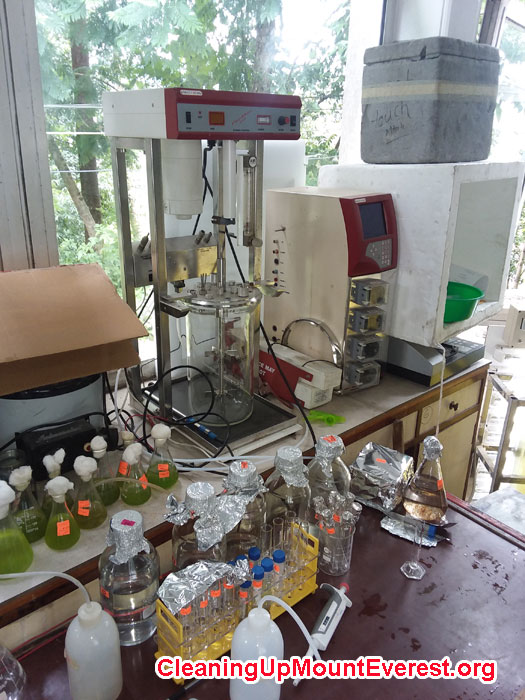

Research undertaken by MEBP and Seattle University (SU) financed a second round of digester experiments at Kathmandu University in 2018. This research supported an MSc student, Mina Pokhrel. The pilot scale tests used blue barrel waste and were operated at mesophilic temperatures (25-30 C). The tests demonstrated biogas production in all four replicates.

The University of Washington and SU collaborated to analyse the microbial ecology of BSP type digesters in Nepal. This work was presented as a poster at the AEESP (Association of Environmental Engineering and Science Professors) conference and is currently being prepared for publication. BMP tests are being conducted at SU to determine the impacts of antibiotics commonly used by climbers on biogas production. Current results indicate little to no impact of the antibiotics. BMP tests are being conducted at SU to identify biodegradable bags that can be used to collect the waste, avoiding the need to macerate them prior to adding into the digester. Three tests have been completed with all bag types showing poor biodegradability. Four new bag types are currently being assessed.

How has your project been impacted by Covid-19?

Construction work in Nepal has been shut down by the Covid-19, stopping the possibility of building the MEBP anytime soon. The world economy has also contracted substantially because of this pandemic. This has slowed most donations to our project, and created a difficult fundraising environment where almost every country has a crisis and people are seeking funding from any source to survive through the year. Any help from UIAA, or its members, to find a funding sponsor would be greatly appreciated. The UIAA has dedicated an area of its donate page for the climbing community to help support the project.

During Covid-19, much of the groundwork in Nepal was put on hold. The team has taken this opportunity to sponsor an internship in the US for an aspiring engineer. This engineer has been working with the architect in the building of a physical construction model. That model will help work out construction sequencing and aid in communicating with the local builders, particularly in the details that are not standard in the local building traditions.

Regarding research, Kathmandu University is willing to start a new round of tests but we have to wait until the pandemic clears. Similarly at Seattle University, the students working with us can no longer work in the lab so that work is effectively on hold.

With access to the Nepalese mountains being restricted, were you nonetheless able to assure progress of your project?

Nepal is currently closed for most travel/construction. As soon as Nepal open from the pandemic, everyone will be hungry to get their industries back into motion. If we are able to fund the project at the time Nepal opens again then our Nepali subcontractors will certainly be happy to construct this project with us.

What are the priorities for the next twelve months?

As soon as Nepal opens and providing our fundraising efforts can continue, then we will finish building the project.

What is the risk that the project stops here and all the hard work over a decade comes to nothing?

From the standpoint of our own organisational (Board) members, the Mount Everest Biogas Project is going forward as the people involved are deeply concerned about this troubling issue. When the Everest climbing expeditions get going again, after Covid, there will be thousands of people using the toilets in base camp and their waste will once more be dumped in unlined pits near the Everest trail. This waste must be treated. The Biogas Project provides an elegant solution. Treat the waste, removing pathogens, and convert it into biogas cooking fuel and fertilizer. We are working very hard to try and raise the money, so that this problem can be solved. If we don’t solve it now, before it is too late, the pits will overflow even more than they are now and contamination will spread from Everest basecamp throughout the entire Khumbu Valley and further poison the Sherpa people and tourists, trekkers, and climbers visiting Everest. On another matter, we have all been working hard to line up all of the necessary paperwork, permits and supporters in the Nepal government and climbing community. This Nepal wide organisational support has been achieved. If for some reason, we are not able to raise the funds soon, then this support may erode as the government changes, and we might have to begin the process all over again, causing further delays and the tragedy of climbers and Sherpas and Nepalese staff’s untreated waste from Everest Base Camp could continue unchecked for many years to come.

What advice would you give to other organisations and/or UIAA members running similar sustainability-led projects? What makes a successful project?

Close coordination with the local people is key to selecting spaces, techniques and collaborators; so as to avoid crossing cultural taboos or overstepping the project’s invitation to alter the community, landscape or how things are done. We must strive to create development projects that address the specific requests of a community, instead of pushing preconceived “solutions” that may impose our culturally informed view of how things should be done. The MEBP is still on guard to avoid these pitfalls, as we continue to pursue implementation of our system for Gorakshep.

How can the general public support/mountaineering community support your project?

Donations to the project from climbers and the public are a very tangible way for people to support this project. But even sharing about our project through social media and other outlets helps to expand our project’s recognition and inch us closer to completing our fundraising goals. Thank you very much for your interest in helping to solve the human waste problem on Mount Everest. We greatly appreciate all that everyone at the UIAA is doing to take care of our world’s mountains!

Cleaning Up Mount Everest Overview

ET CONTRIBUTORS|Nov 03, 2018 by Shail Desai

toilet tent at basecamp. tents and views. Photo M Williams

At one end of Kathmandu University is an isolated structure that is not too popular with the students. A few signs on the door announce “Human faecal matter”, “Highly contagious” and “Do not enter”. Those working inside, led by Bed Mani Dahal, associate professor of the Department of Environmental Science & Engineering, could hardly disagree with the revulsion caused by the project his team is associated with.

“You don’t really feel comfortable when you are working with human faeces — the smell is the worst part of it. Precautions are a must because you can also get easily infected,” Dahal says, smiling.

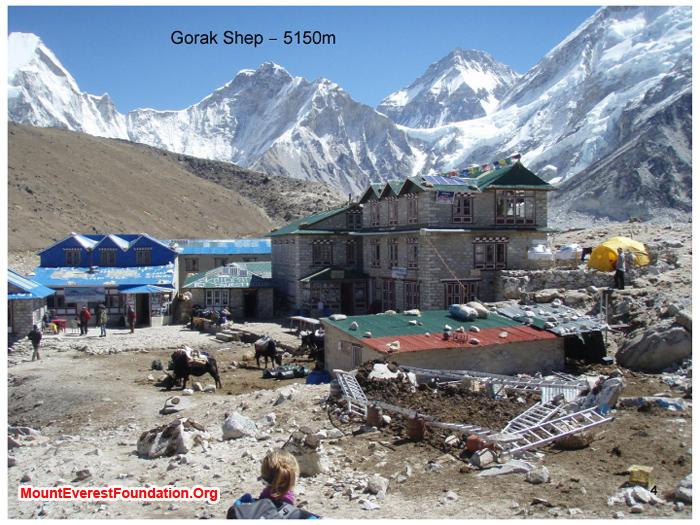

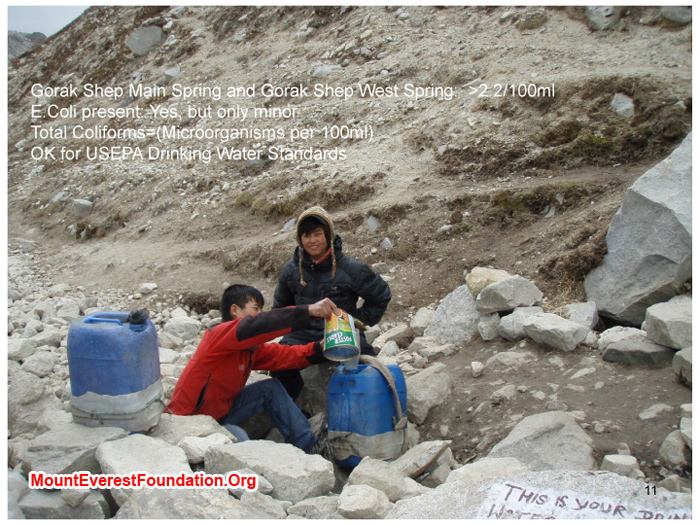

It’s just another day in the life of the researchers, from Kathmandu University and , who are associated with the Mt Everest Biogas Seattle University Project that looks to address the poop issue on the highest mountain in the world. According to the records of the NGO, Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee, around 12,000 kg of human waste is generated each year on Everest, 80% of which is produced in the spring climbing season alone (April-June). This waste is carried off the mountain and down to the village of Gorak Shep in Nepal — the first human settlement for those descending the mountain, after the Everest base camp — where it is simply dumped in unlined pits in the area, leading to serious issues of contamination.

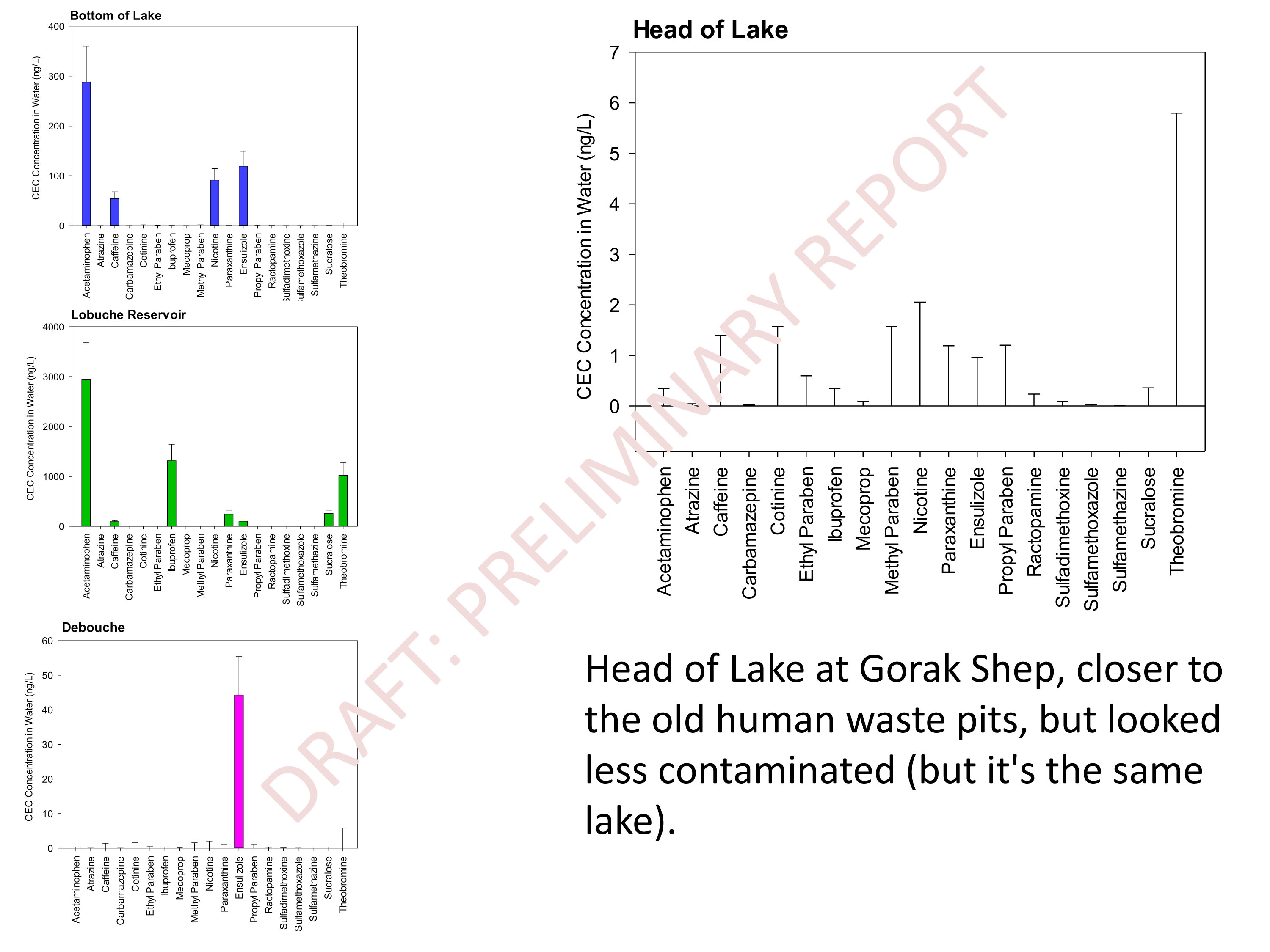

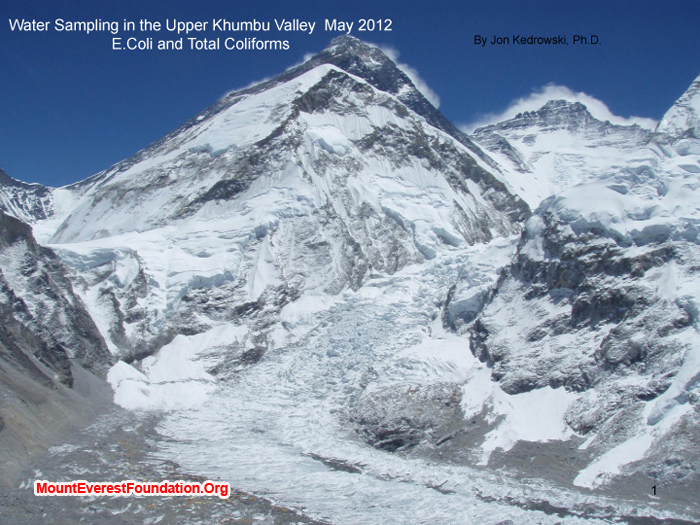

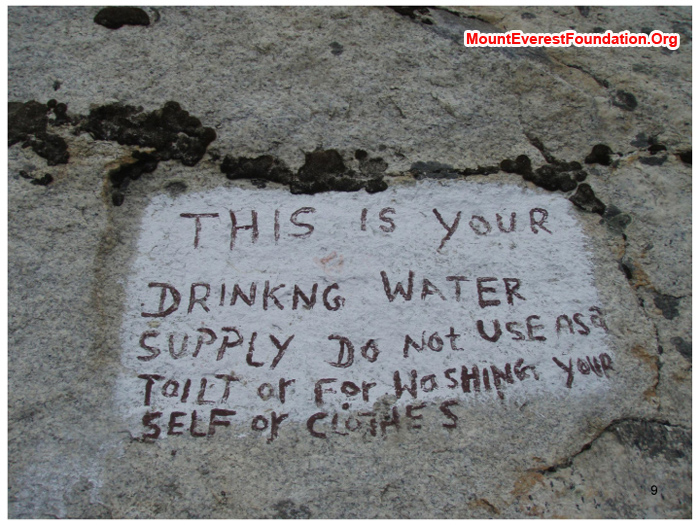

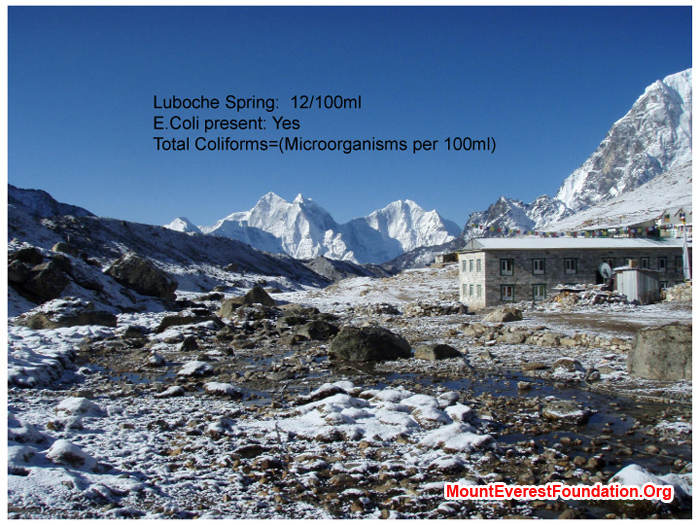

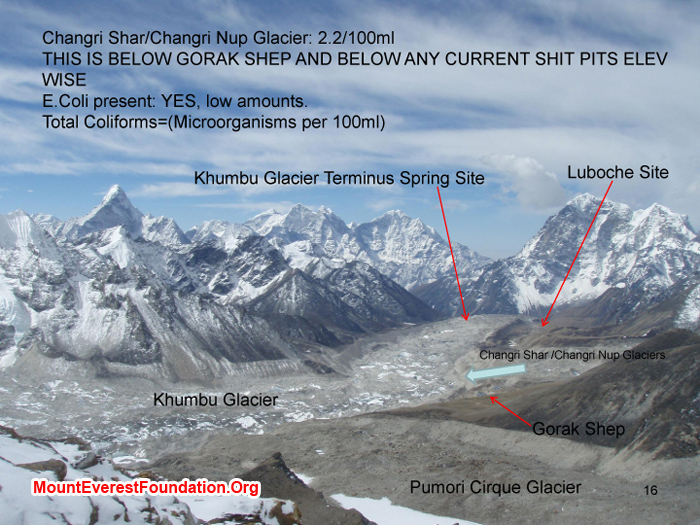

“When water seeps through the ground, it looks clean because it’s filtered through the soil. But it has a lot of pathogens due to this human waste, which makes it unsafe for the local community,” says Michael Marsolek, associate professor at Seattle University.

The idea to find a solution was first conceived around a decade ago. Dan Mazur, an American mountain guide who leads expeditions up Everest, was all too aware of the impending problem, ever since commercial expeditions took off in the early ’90s. According to The Himalayan Database, while there were 77 successful ascents between 1985 and 1989, that figure escalated to 634 in 2015-17. Add to that the expedition support staff, and Everest sees a civilisation at base camp during the climbing season each year. Mazur got together with Garry Porter from Engineers Without Borders to conceptualise a biodigester that could convert the human waste into methane gas, which could be used by the local community for cooking.

This would also reduce their dependency on other fuels. With a little treatment, the residue left behind could also be used as fertilisers.

“Cutting of wood for fuel led to defoliation wherever there was vegetation. Besides, homes burning wood or yak dung led to inhabitants getting pulmonary diseases,” Porter says. “The design of the bio-digester was deliberately made open source, so that it can be replicated and it has drawn interest from organisations in Pakistan and Iran as well.”

The concept isn’t novel in terms of implementation. In the lower reaches of Nepal, around 3,00,000 bio-digesters process faecal waste, animal dung and crop residue to cater to the needs of rural households. In fact, the Nepal government even provides subsidies for the installation through the biogas support programme. But at higher elevation, the altitude and the erratic weather patterns add to the challenge. “Bacteria can easily break down mixed waste, as compared to solely faecal matter. And at those heights, the process takes longer,” Marsolek explains.

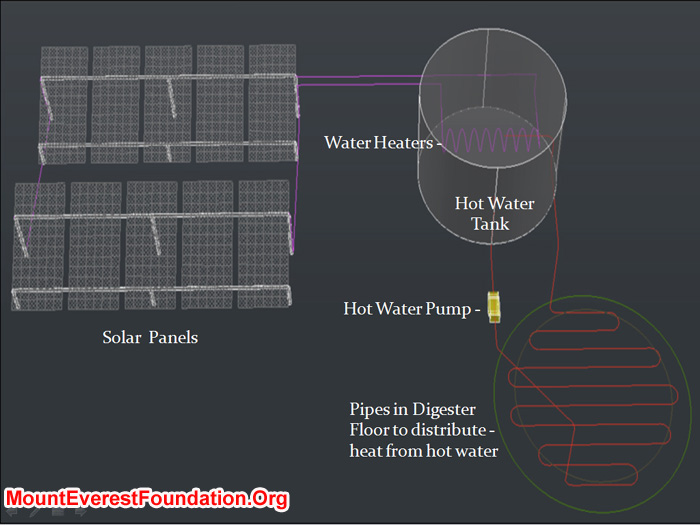

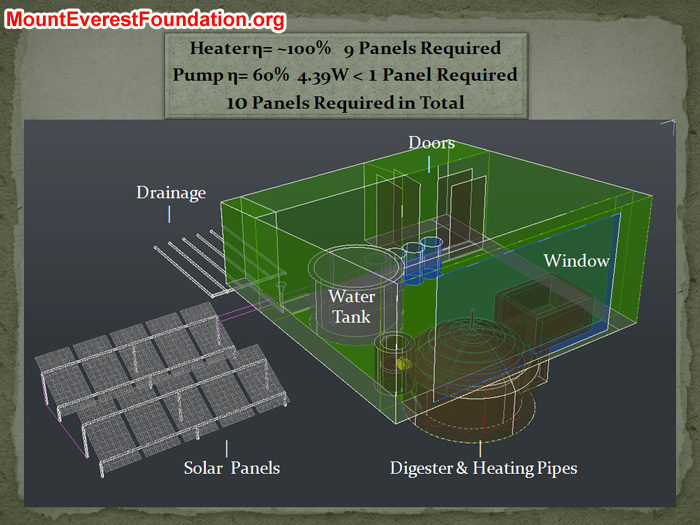

Over the last four years, the team has worked on a bio-digester design that exclusively processes human waste. The facility at Kathmandu University was then used to simulate conditions on the mountain to understand the optimum temperature at which microorganisms could break down the waste and produce adequate biogas. On the mountain, solar panels would help a bio-digester maintain suitable temperatures. “Researchers have been able to generate biogas at high temperatures, but they’ve not had much success in low-temperature areas. This is the main constraint, so we spent a lot of time on the design of an insulated greenhouse and regulating temperature inside it. We’ve had success in the lab and now look to scale up,” Dahal says.

A major aspect of their work has been fundraising — for the research, as well as to construct the facility at Gorak Shep. So far, a crowdfunding campaign has managed to raise around $2,600 in nine months. The project was also awarded the UIAA Mountain Project Award last year, which earned them a grant of $5,000. “It’s hard to arrive at a figure until we start building. But if a bag of cement costs Rs 1,500 in Kathmandu, it’s about Rs 20,000 up in the mountain. A porter must carry it for two weeks to get it there, else it has to be ferried by helicopter, which is $2,400 an hour. At least two-thirds of the total cost is transportation,” Mazur says.

Once in operation, the project will provide fuel for the local community and will address the environmental hazard on Everest. It will also generate employment as people would have to be hired to maintain the bio-digester and the pipelines distributing the gas. “One problem with these humanitarian engineering projects is that they are not monitored for a long time, so our fundraising accounts for this as well,” Marsolek says.

If the funds are gathered, the project could be implemented as soon as monsoon next year. “The great thing about Mt Everest is that there’s a lot of appeal — there’s only one Everest, after all. And we hope that will encourage others to join in,” Mazur says.

So Porter, along with fellow climber Dan Mazur, established the Mount Everest Biogas Project almost eight years ago to try get rid of this "environmental hazard."

Over the years they have been toying with the idea of installing a biogas digester at Gorak Shep to convert human waste into methane gas.

While biogas digesters are used around the world, and fairly easy to make, they are difficult to operate at altitude in sub-zero temperatures.

This is because the process requires bacteria to feed on organic waste, and these living microorganisms need to be kept warm, explains Porter.

The Mount Everest Biogas Project plans to use a solar array panel to transmit heat into the digester. There will also be a battery array to store energy at night when the sun sets.

Rendering of the proposed biogas digester.

The end products will be methane gas, which can be used for cooking or lighting, and effluent that can be used as fertilizer for crops.

"It takes a nasty product and makes two products that can be used by the Nepali people," explains Porter.

However, Porter says climbers often take antibiotics, and he was initially concerned that antibiotics in the poop might impact the microbes' ability to break down the waste.

But he says mini digesters at Kathmandu University successfully converted human waste from base camp to methane gas.

The Economist -

How to dispose of human waste on Mount Everest. Unsavoury problems at 18,000 feet

Oct 25th 2018 | GORAKSHEP | By Kaitlin Tosh

“Take only memories, leave only footprints” is more than a clichéd hiking motto at the Sagarmatha National Park in Nepal. The large box of rocks sitting next to the metal detector at the local airport is a testament to that: tourists departing from Mount Everest have to dispose of material they have collected before stepping onto the dauntingly short runway. Fulfilling the second half of this mantra, however, is harder. Tens of thousands of tourists leave more than just footprints. They have created a mountain of faeces, which is becoming an environmental problem.

In 2017, 648 people reached Everest’s summit, more than seven times the number two decades ago. Many more make it to base camp. Currently, toilet waste is carried and dumped into pits near the town of Gorakshep, an hour’s walk down the mountain. The amount of waste is increasing fast, says Budhi Bahadur Sarkhi, a porter who has been carrying poo from base camp to these pits for 12 years. When Mr Sarkhi started there were seven porters hired for the job. Now there are 30.

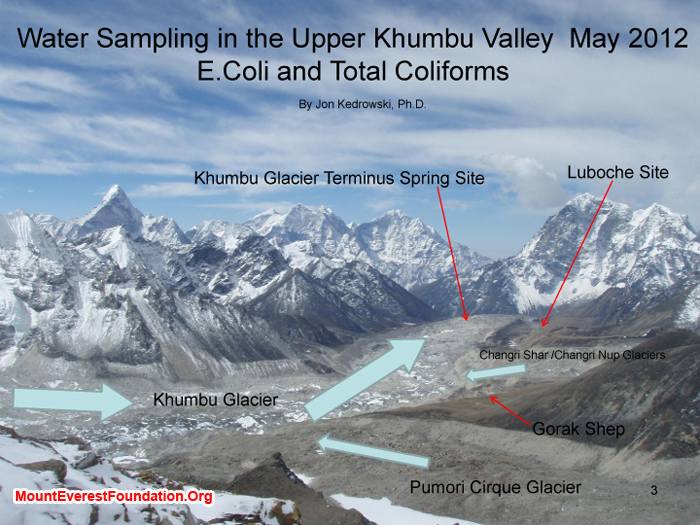

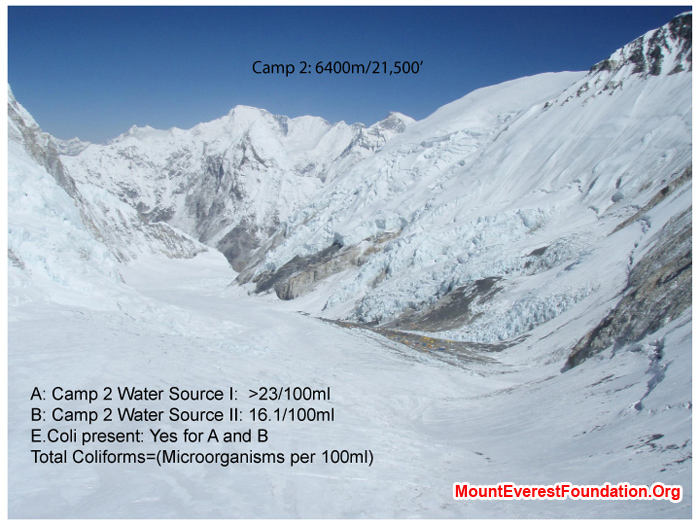

Dumping sites are filling up quickly, and the run-off is infiltrating the region’s water channels, some of which feed into wells that supply drinking water. When tests were done at nine water sources in the region, seven were contaminated with significant levels of E. coli. The presence of human by-products in the water, like nicotine and sunscreen, suggests that the contamination came from human faeces, rather than that of the many local yaks.

One innovative solution could help. The Mount Everest Biogas Project, led by two mountaineers, hopes to install a biogas reactor in Gorakshep at the start of next year. All of the faeces from base camp would then be converted into two by-products: fertiliser and methane gas, possibly for cooking. In which case the mountain would be a little less brown and a little more green. For more information: www.MtEverestBiogasProject.org

This article appeared in the International section of the print edition under the headline "A mountain of waste"

Everest Base Camp Waste Treatment Research Collaboration Between Kathmandu University and Seattle University: www.CleaningUpMountEverest.org .

Researchers from the 2 Universities are now in Kathmandu and working together to build a waste treatment plant for Everest Base Camp.

Biogas Laboratory at Kathmandu University. Professor Bed Mani (KU), and Mike Marsolek (SU) in front of portable biogas digester

Professor Bed Mani (KU), and Mike Marsolek (SU) in front of the new Everest Base Camp Waste Treatment Research Building at Kathmandu University. KU Grad Student Garima Baral and Professor Bed Mani (KU), and Mike Marsolek (SU) discussing biogas research.

Professors Sunil Prasad (KU), Mike Marsolek (SU), and Bed Mani discuss Everest Base Camp Waste Treatment Research. KU Grad Student Garima Baral, and Mike Marsolek (SU) Looking at Biogas Research Setup at Kathmandu University.

By Katy Scott, CNN - August 6, 2018 - Solving Everest's mounting poop problem

The human impact on Everest (CNN)When climbing enthusiasts take a stab at the highest mountain in the world, thinking about their bodily waste is probably low on their list of priorities.

This season, porters working on Everest schlepped 28,000 pounds of human waste — the equivalent weight of two fully-grown elephants -- from base camp down to a nearby dumping site, according to the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC), a local NGO tasked with cleaning up Everest.

At Gorak Shep, a frozen lakebed 17,000 feet above sea level, waste matter is dumped in open pits where it shrivels and dehydrates. But there is a risk that it will leak into a river and contaminate the water supply system, explains Garry Porter, a retired mountaineer and engineer from Washington state.

"It's unsightly and unsanitary, it's a health issue and an environmental nightmare," Porter tells CNN.

"I experienced the thrill and grandeur of Mount Everest, but I also saw what happens when we, the Western world, leave, as if our waste doesn't stink."

But Porter doesn't fault climbers, as he says their main preoccupation is summiting and returning home in one piece.

Nor are Nepalese authorities to blame, says Porter, as there are no waste treatment plants nearby.

Yangji Doma, of the SPCC, agrees that the current human waste management system is problematic.

"We make sure that it's not dumped on the glacier itself," she tells CNN. "But the main problem is ... it's very cold and it doesn't naturally degrade, we understand that. It's managed but it's not sustainably managed."

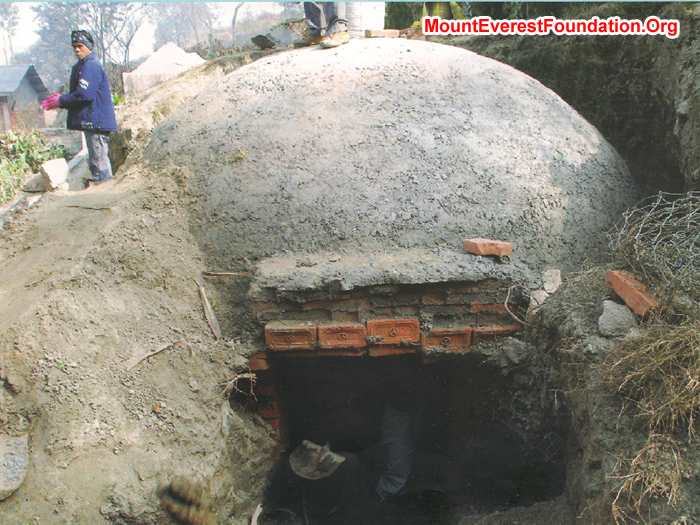

Photo Bio Gas Digester

So Porter, along with fellow climber Dan Mazur, established the Mount Everest Biogas Project almost eight years ago to try get rid of this "environmental hazard."

Over the years they have been toying with the idea of installing a biogas digester at Gorak Shep to convert human waste into methane gas.

While biogas digesters are used around the world, and fairly easy to make, they are difficult to operate at altitude in sub-zero temperatures.

This is because the process requires bacteria to feed on organic waste, and these living microorganisms need to be kept warm, explains Porter.

The Mount Everest Biogas Project plans to use a solar array panel to transmit heat into the digester. There will also be a battery array to store energy at night when the sun sets.

Rendering of the proposed biogas digester.

The end products will be methane gas, which can be used for cooking or lighting, and effluent that can be used as fertilizer for crops.

"It takes a nasty product and makes two products that can be used by the Nepali people," explains Porter.

However, Porter says climbers often take antibiotics, and he was initially concerned that antibiotics in the poop might impact the microbes' ability to break down the waste.

But he says mini digesters at Kathmandu University successfully converted human waste from base camp to methane gas.

The team still needs to test whether the effluent will be free of hazardous microorganisms and therefore safe to use as fertilizer. Porter says they will begin testing the effluent this year and if it is dangerous, the plan is to filter out contaminants in an underground septic system.

Read: Rebuilding a Nepali village, one block at a time

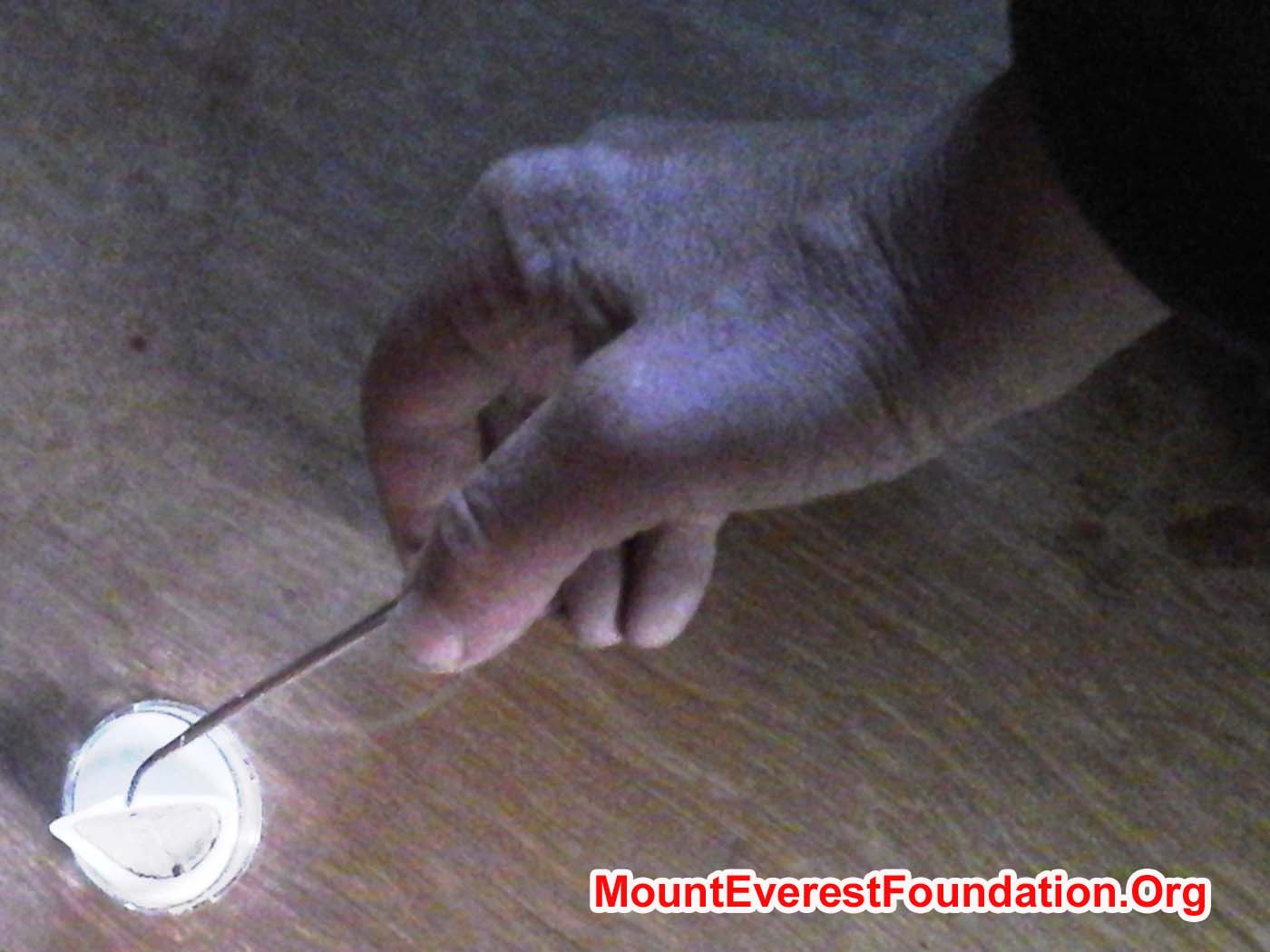

Researchers from the Mount Everest Biogas Project test soil at Gorak Shep.

The Mount Everest Biogas Project has a signed agreement with the SPCC and is ready to break ground once they have raised the necessary funds.

Porter estimates that the first digester will cost around $500,000, mostly because of the transportation cost to lug the materials up to Gorak Shep.

Thereafter the cost will come down and Porter plans to "hand the keys" to the SPCC.

Doma hopes the project will be a success: "It is a very innovative solution to address human waste in the long run, because right now the way we do it is not that good. It is not sustainable."

For Porter, it is about paying off a debt to the Nepalese people.

"I was part of the problem, so hopefully now I can be part of the solution," he says.

Mount Everest Biogas Project was announced as the overall winner of the 2017 UIAA Mountain Protection Award during the UIAA General Assembly in Shiraz on Saturday 21 October.

The United States-based project is a volunteer-run, non-profit organization that has designed an environmentally sustainable solution to the impact of human waste on Mt. Everest and other high altitude locations. The Mount Everest Biogas Project (MEBP) is the fifth winner of the annual Award joining projects from Ethiopia, Tajikistan, Nepal and France.

The Mount Everest Biogas Project is a deserving winner of the Award,” explained UIAA Mountain Protection Commission President Dr Carolina Adler. “Waste in the mountains is a real problem that calls for implementation of solutions to address and test it under often very challenging environmental and social conditions.”

Stephen Goodwin, member of the UIAA Mountain Protection Commission, a vice-president of the Alpine Club (UK), and one of the Award assessors, added: “The Mount Everest Biogas Project project perfectly meets the aims of our Commission in that it is clearing up the waste of mountaineers and trekkers in an iconic location. There are multiple benefits for the “downstream” Sherpa population (notably less polluted water) and providing the project proves a success this technology can be applied to other high altitude mountain locations where climbers and/or trekkers have created a waste disposal problem.”

For the Award winners themselves, this is recognition for seven years of intense work and development towards helping resolve the major issue of ‘what to do with human waste in an extreme environment’. Garry Porter, one of the project’s co-founders, explains the potential benefits of winning the Award: “The Mountain Protection Award is a huge morale boost to our volunteer team members because it acknowledges their efforts in addressing a solution to the issue of human waste in mountains. The prestige of an endorsement by the UIAA will provide a major boost to our fundraising effort.”

Please watch New Video of Keeping Mount Everest Pristine with Mike Marsolek

Please watch New Video of Mt. Everest Biogas Project-Converting human waste to metha

Please watch New video of, Professors Making Biogas in the Laboratory at Kathmandu University.

The Mt Everest Biogas Project kicks off their fall fundraiser with this exciting news. Please show you care about cleaning up human waste on Everest!! Get involved today at:

Cleaning Up Mount Everest Archive

Proposed Location and Design of Everest Base Camp Biogas Shelter in Gorak Shep, by Joseph Swain.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

CLEANING UP MT. EVEREST (Converting poop to power)

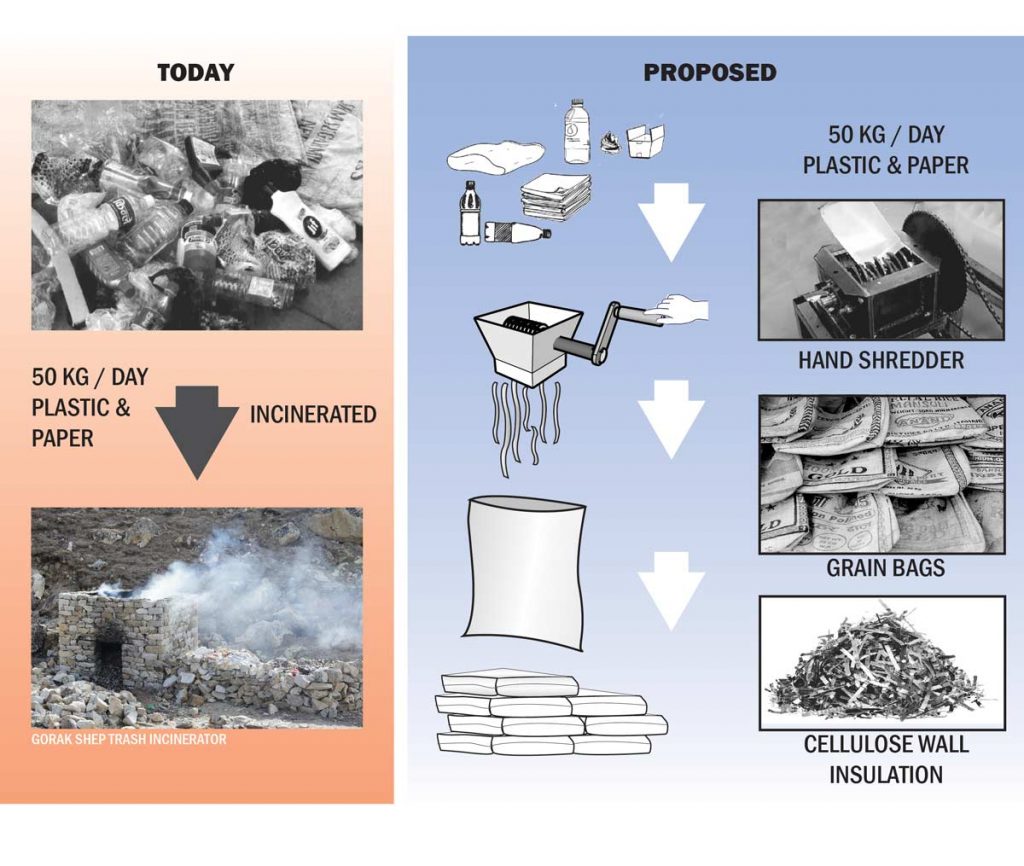

Climber decending to southcol after summit. Photo Mike Fairman. Just a bit of the rubbish collected from basecamp and Gorak Shep being burned and processed for transport to lower altitude.

Climber decending to southcol after summit. Photo Mike Fairman. Just a bit of the rubbish collected from basecamp and Gorak Shep being burned and processed for transport to lower altitude.

Thanks to the support of many of you who have been following this campaign, the Mt. Everest biogas project volunteers made the trip to Nepal and ultimately to Mt. Everest base camp for a few of us. We have been back for a little over 2 months and I want to update everyone on the incredible progress that we made on this trip. It is hard to know where to start other than by saying that we accomplished more in this trip than anyone ever expected. And it would not have been possible without the generous contributions of many of you.

So let me summarize the trip first and then provide a link to our new Facebook page that was developed along the way to Everest base camp by one of the volunteers on the trip. She writes much better than I, so bear with me while I try to summarize what was accomplished. So here goes.

A major milestone was achieved when we met formally with the two agencies Sagamartha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) and Buffer Zone Committee (BZC) that control who and what can be built within the Mt. Everest National park. This was a key meeting in that the biogas project needed their approval to build at Gorak Shep or all the design effort over the past 6 years would be for naught. We met in Namche Bazar, they listened, they liked what we were proposing to do and they signed a three party memorandum of understanding with us. Equally important, they agreed to take ownership of the biogas system following construction at Gorak Shep which was a critical "exit strategy" for the team. We were elated after the meeting because this was the formal go ahead we needed.

Basecamp panaroma at trekkers rock. Mike Fairman Photo

Then on to Gorak Shep and along the way, we met with other members of BZC and ultimately the teahouse owners at Gorak Shep. Incredible support from everyone we talked to. We were flying high by the time we got to Gorak Shep even though we were at 17,000' and the elevation was starting to show its affect on us.

At Gorak Shep, we briefed the teahouse owners on the design and then laid out the planned location of the biogas system. Part of the plan was to dig a 6' deep hole to run water infiltration tests but unless you are fully acclimated to the altitude, that is a tougher job than we planned. Fortunately, 8 young volunteers from the tea houses helped us and in 3 hours it was done. Then on to Everest base camp before heading down mountain. Anyway you cut it, the hike/trek to Gorak Shep is tough. Hiking down is not much easier because the distance still has to be covered.

Back in Kathmandu, the trekking team met the rest of the biogas team who had been meeting with potential subcontractors and re-affirming their interest in the project.

One final stop at Kathmandu University before heading home. It has been the intent of the project to ultimately involve the academic community in the biogas project A Seattle University engineering professor, who is part of the biogas team, has established a formal relationship between Seattle University and Kathmandu University to conduct lab/bench level tests of the actual human waste from Everest base camp. The project has predicted performance data but the testing and resultant test data would answer the question, "will the system work at Gorak Shep"? The testing started a year ago, shortly after the earthquake in Nepal and the students have struggled with the project. Not exactly a pleasant engineering test program but they persevered and when we were there, they showed us clean burning methane gas produced from the human waste from base camp. Great way to finish the trip.

Ascending team overtakes descending team on Lhotse Face. Franz Ruehrlinger Photo. Camp 1 with Mount Lhotse in background. Mike Fairman Photo. Climbers on the Lhotse Face. Mike Fairman Photo

For a much more detailed day by day trip report, please go to the new Facebook account called The Mt. Everest Biogas project. Lots of pictures and written with great enthusiasm by one of the team members, Brenda Bednar. I hope you enjoy her writing and can feel the excitement that we felt.

I will try to provide more frequent updates as we move into the next critical phase of the project: fund raising for the construction at Gorak Shep. If we are successful in raising the funds, construction could start as early as next spring.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gorekshep is going to base for Biogas. Measuring the area at gorekshep. Photo Joe Swain

Working hard for BioGas project at Gorekshep

On going research. Research for the soil test.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Nepal 2016 Running Journal The Mt. Everest Biogas Project : Joseph Swain, Project Lead, Architects Without Borders-Seattle

This is a daily log of the May 4-26, 2016 trip to Nepal by MEBP team members Garry Porter and Joseph Swain, along with travel companion and Honorary Social-Media Coordinator Brenda Bednar. As availability of internet and computers will be inconsistent on the 17-day trek through the Khumbu Valley, posts will be written daily but uploaded when possible. Posts will eventually make it to the project website, facebook page, funding page, etc., along with photos.

Everest, Nuptse seen from Kalapather. Trekking to Everest Basecamp

Yak carrying load to Everest Base Camp Waste store at Gorekshep Wednesday,

May 25

On Monday I had gotten in touch with an American-Nepali NGO called Portal that is working in Kathmandu. They started out a couple of years ago fabricating custom utility bicycles that could transport large loads, gas cans, corn huskers, etc., and selling them to locals who needed them subsidized and on micro credit. I was interested in working with them to develop a method for converting the excess paper and plastic bottle waste up at Gorak Shep into a form of cellulose insulation.

Our design currently calls for a thick cavity wall for site-manufactured insulation of about R-1 per inch, and the assumption is that we can shred the trash into fine enough strips and place them into a the ubiquitous rice or utility bags to make insulation "pillows" for the cavity wall. My thought was that if Portal could make a pedal-operated corn husker, they might also be able to create a pedal-operated paper and plastic shredder that we could wheel up to Gorak Shep.

I met Caleb Spear, Portal's Executive Director, at their steelyard/workshop early int he morning. Their yard was full of steel wide flanges, which will soon be part of their new workshop/warehouse. I soon learned that after the earthquake last year, Portal switched gears, so to speak, from bike design to emergency and permanent steel shelters. They have some prototype quonset-style shelters in their yard which are little more than steel pipe and corrugated metal sheets, but can be transported in a truck and erected extremely quickly. They also have a permanent kit that consists of frames, chainlink fencing, and corrugeted metal roofing. The frames are welded and bolted HSS, about 2"x2". The prefab systems are impressive not only in their compactness, but also the speed in which they weere designed and developed. Caleb said they have more than one hundered orders for the more permanent shelters, but they are on hold because of a bottleneck at the government approval level. This was a common theme with respect to relief efforts throughout our visit to Nepal - there are a lot of resources and hands ready to help, but the government can't act quickly enough.

Portal has a handful of workers and interns who can cut, weld and fabricate steel parts, most of whom are from very disadvantaged families in the area. There are a handful of westerners, some of whom are volunteers. As we talked about construction and steel fabrication in Nepal I helped the entire crew of about 10 reorganize and move their steel wide flanges by hand. I hadn't planned on doing any physical labor during my meeting, but it felt good to get some sort of workout in, as this was my fourth day in Kathmandu and I was feeling energetic, thanks to all the oxygen here (despite stores selling running and workout gear in Thamel, there aren't any good places to go running in the city, according to Mingma).

I showed our MEBP designs to Caleb and Emily, another American who was working on site. They were generally supportive and liked the idea of creating a pedal-powered shredder for our insulation. Caleb said the mechanism would be pretty simple to build, and changing gears could mean we could control how much speed or torque we put into the shredding attachment. What that attachment would be remains to be seen. He sent me to a local market where I took some photos of some off-the-shelf hand-operated grinders and such.

The cost of building a bike-shredder to Portal's standards would probably be in the $300 range. Caleb also thought the idea of trusses site-fabricated out of smaller pieces and bolts could work. I liked this idea because it would mean we would be using less wood, a rare resource in the upper valley, and we may be able to get a longer span for the same transported weight. Portal also seemed like a great place to look if we need custom-fabricated steel parts, say, for steel-to-stone attachments. Being able to communicate with them in English could be huge when we are under construction. When we have a better idea of our construction timeline, I will be in touch with them about these things.

After my meeting with Portal, I went back to the hotel to pack and run some errands with Brenda. In the meantime, Kirk, Garry, Nate and Mingma met the researchers at Kathmandu University and with engineers at Gham Power. Both meeting went very well, particularly at KU. One of our last hurdles (after getting our partnerships and approvals hammered out the previous few weeks) before fundraising was the looming question of whether we could get actual climber waste to break down and produce methane in a controlled environment. In May of 2015, Mike Marselek had gone to KU for us to set up some experiments with climber waste transported down from EBC by Dan. As of last month, there had been no measurable amount of methane. However, in the past few weeks, some new experiments using dow dung as a starter innoculum have allowed the climber waste to produce a significant amount of methane. I was told Mingma has a video of it burning in the lab on his cellphone. In any case, this is great news for the project. We will need to write about this more in-depth in a later post.

With all this exciting news, it was hard to believe that we had to leave today, but Garry took off at 7pm tonight and Brenda and I flew out of Kathmandu at 11:15pm. Kirk and Nate will be in the city until Saturday to finish their round of meetings. Everyone agreed that it has been a fruitful couple of days, especially with the entire team overlapping in one place.

Team reach Everest Basecamp. Team working at Gorek Shep Everest Cleanup project. Tuesday,

May 24

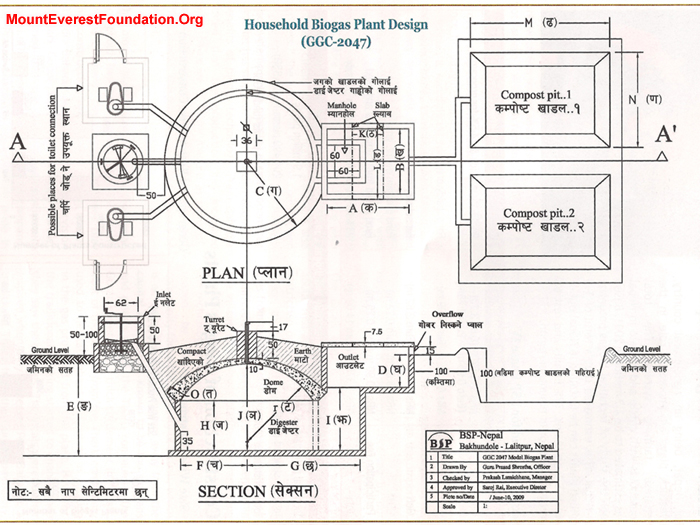

Kirk and Nate had scheduled a big meeting with the Biogas Support Partnership - Nepal organization (BSP-Nepal) that has overseen the construction of thousands of biogas digesters in the country. BSP provides support, expertise and instruction to communities and builders, but is not in the business of building biogas plants themselves.

Kirk, Mingma, Garry, Nate and I had an early lunch meeting to go over the agenda and what we hoped to accomplish before heading out to BSP's offices. Our primary goal was to get a nod of approval for our technical strategies and an agreement that we could move forward with the design with the expectation that BSP would provide their support services at Gorak Shep.

Overall the meeting went very well. We met with an assistant director, Mr. Prakash Lamichhane, who expressed excitement over the project, especially the prospect of building a "historic" working biogas system at 17,000 ft. Kirk summarized other points of the meeting as follows:

In the evening, the entire team went out for a celebration dinner with Mingma and his family, as Garry, Brenda and I are to leave the next day. We went to a family restaurant of Mingma's choosing, Alice, where we tried an array of Nepali specialties, including several thali sets, curries, momos (spinach and buckwheat) and soups. We were joined by the head of the Khumjung Buffer Zone Committee, who happened to be an old classmate of Mingma's. As a thank-you gift, Brenda and I had had t-shirts custom stitched with the MEBP logo (or a close apprximation) by a local embroiderer. Garry presented these to everyone, including Mingma's family, alongside some smoked salmon from Seattle.

Bit of rubbish at Gorek shep. Everest Cleanup project team working at Gorek Shep.

Monday, May 23

Due to a snafu at the Dubai airport, Nate won't be making it to Kathmandu until this evening. We only had a meeting with Gham Power scheduled for this afternoon, which Nate was able to change to Wednesday instead.

Kirk had booked Mingm's wife as a tour guide for Sarah and Nick, her boyfriend, but Sarah was feeling under the weather, so Kirk invited Brenda and me to go on a half-day tough of the main sights in the city. We first walked through some of the older markets and checked out Durbar Square, a World Heritage site that sustained some serious earthquare damage last year. There hasn't been a lot of permanent rebuilding yet, but one can see masonry walls of nearly all the buildings proppsed up with either steel or wood buttresses. We took a cab to the Boudah Stupa, one of the biggest stupas in the world. It takes about 10-15 minutes to walk around once (clockwise), and we did three laps. This World Heritage site also sustained some damage at the top (the "lotus" and the" pinnacle") but the dome was more or less intact. There was some very impressive wood scaffolding set up on one part of the done to facilitate moving bricks and cement up to the top. It reminded me of the renderings of how Egyptian pyramids might have been built thousands of years ago.

In the evening Mingma and his family met us at our hotel and we walked to a nearby Italian restaurant for dinner. It may have been because we were still coming off of more than two weeks of teahouse food, but the pizzas and salads were incredibly good. Nate landed around 5pm and Mingma picked him up and brought him to the restaurant in time to eat everyone's leftovers.

After a 30-min flight, we landed and grabbed a taxi to our new hotel, the Kantipur Temple House, a hotel Kirk and his daughter, Sarah, were staying at. The place is a little oasis on the edge of the busy Thamel district, with a generous courtyard and garden separating it from the street, and beautiful carved wood and brick details everywhere. It's reminiscent of some Indian Heritage hotels in the architectural quality and service - there are no TVs or AC in the rooms, not that they would be necessary - though the building itself is only 19 years old.

A warm shower and a nap had us feeling like completely new people after 15 days of trekking with the occasional shower. Kirk was waiting for us in the courtyard when we arrived and Garry caught him up on our adventures. We all got together in the evening to make new plans for the coming week over drinks and dinner, though Nate doesn't get in untl late tonight.

Memorial. Mingma with local for Everest Cleanup project

Sunday, May 22

Mingma was able to secure four seats on a Goma Airlines flight from Lukla to Kathmandu one day earlier than we had planned, so we were up early and were racing down the 18% runway by 8:45am. The sensation was similar to a roller coaster, except when you expect the plane to drop off the end into the valley below, it instead levels out and everyone breathes a sign or relief.

Saturday, May 21

We are exactly one day ahead of schedule at this point. We left Namche Bazaar early to take advantage of the perfect trekking weather - fairly warm and dry. We saw some a famiy of Himalayan tahrs across the river as we walked, as well as some birds we'll have to look up once we get home. After descending down to Phakding for lunch, the sky clouded up. The final three hours of our 15-day trek turned out to be pretty tough, as the route turned uphill and for the first time we experienced high humidity in the valley.

The skies opened up just as we entered Lukla, and we speed-walked through the main street to our last teahouse. It didn't matter that our clothes got wet and muddy, as nearly every piece of clothing we owned was worn through to the end of its socially-acceptable life.

Before dinner, Mingma had us put cash in two envelopes for our porters for tips (about $90 each) and led a semi-formal presentation for us that essentially released the porters from their duties. After dinner, Garry, Brenda and I went to bed early, as we needed to be at the airport to catch our flight out of the Khumbu to Kathmandu (weather permitting).

Everest Cleanup project. Gorek Shep Everest Cleanup project.

Friday, May 20

We were all up early on Friday for a 9am meeting with the presidents of the SPCC and BZC, a follow-up to our initial meeting the week before. Mr. Ang Dorjee, the SPCC president, gave us only one minor edit to Mingma, so I ran down to the nearest internet cafe and made the change (the official name of the BZC is the Sagarmatha National Park Buffer Zone Management Committee). A few minutes later we were all shaking hands over sweetened nescafe and signing the MOU documenting the partnership between our three organizations.

By 9:30am our work was done and Garry went to scan the documents and send out the good news. Everyone else took the rest of the day to go shop for souveniers, catch up on emails (Namche was the first reliable internet we have had since .... Namche), and rest up. Nine straight days of hard trekking had caught up to us, and our legs appreciated the day off. Garry also handed his boots off to a cobbler who promised to fix the soles before we left the next morning.

At dinner we celebrated our progress with the Nepalis over yak steaks and Sherpa beer. (Of all the beer we had tried in Nepal thus far, this is our favorite, though it's still a pretty light kolsch-style beer that may or may not be brewed by Sherpas).

Re-construction need for stupa. Research process at Gorek Shep.

Thursday, May 19

On our way out of Phortse we stopped by the Khumbu Climbing Center. The two-story steel structure is still going up, though most of the first-floor structure is in place now. The site was buzzing with workers, and the site supervisor, Brandon Lampley, was extremely helpful in showing us what can be done in the region, construction-wise. Brandon has a background in the historic preservation and renovation of older masonry buildings in the US, and he said he's been working his whole life to be prepared for this project. Some things we learned from our 90 minutes on site included:

The Nepalis are excellent at problem solving and figuring out new and custom solutions when confronted with a problem, for example, fabricated steel parts.

The cost of a single, perfectly square and flat stone in a masonry wall is about $15-20, as it takes a skilled stone cutter an entire day at about $15/day.

The cost of a decent structural stone without the crisp, square finish is about 1/6 of the perfectly square stone.

Cutting stone is hard on the tools. The KCC team keeps a forge going 24 hours a day to hone their chisels.

Cutting stone is hard on the hands. I found this out after ten minutes of trying to chisel out a flat plan on a rough stone. Carpel tunnel must be one of the more common occupational diseases of the trade.

Steel parts can be fabricated in Kathmandu, as long as one can communicate the design.

Most everything comes from Kathmandu, including cement. However, for slightly less cost, one can sometimes get common materials at the air strip above Namche Bazaar.

Cement costs about $35 per bag in Phortse.

XPS (blue) foam rigid insulation is available in Kathmandu. The thickness KCC was using was around 3cm.

Wire mesh for gabion retaining walls can be woven on site with a makeshift loom and galvanized wire. It's cheaper to carry a roll of wire up the mountain than a pre-welded mesh.

The building season halts from July through September for cultural and religious reasons.

There was plenty more that we picked up, but this was some of the more pragmatic information.

From Phortse we trekked down to the Dudh River to cross and then up an interrupted 1,300 feet to Mong La, a small outpost with great views and a few teahouses. We had a light lunch of curry and dal and then decended slowly to Namche Bazaar. We stayed at the Mountain View Lodge, which is next to Mingma's childhood house. His parents joined him for a momo dinner there (the yak momos were some of the best momos we have had on the trip).

Rubbish were burned in Gorek Shep. Bring water in Tent.

Wednesday, May 18

Today was a straightforward day of trekking down the valley. We took a different route than the way we came up because we wanted to check out the Khumbu Climbing Center in Phortse, an ongoing construction project that was developed by the Alex Lowe Foundation and designed by students at the University of Montana. The two-story structure was designed to US standards, with steel structure and masonry walls. We arrived in Phortse too late (and just before a huge rainstorm) to check out the KCC, so we rested up for the trek tomorrow.

Tuesday, May 17

Twelve hours and 23km brought us from Gorak Shep to Everest Base Camp (17,200 ft) and then down to Pheriche (14,000 ft). Today featured a temperature swing from around freezing to blazing hot coming down from the glacier and back to a snowstorm for the final 90 minutes of trekking.

We arrived at EBC after about two hours of walking, and the camp mostly lived up to its reputation of disappointing thousands of trekkers every year. The glacier is covered with hundreds of tents from all corners of the world. We didn't see many climbers, just a few staff, as most everyone has either summited already or is on the upper mountain for a summit attempt. The most interesting things are the stonehenge-like ice structures that make up the exposed part of the glacier, as well as the massive boulders precariously perched on top of slowly melting ice pillars.

We slogged through the rock-chip path that winds between the camps until we found Dan Mazur's Summit Climb camp. Dan is a founder of the MEBP alongside Garry. Dan was leading his group of 10 climbers up around Camp 2 at the time, but we were able to say hi to him from the camp radio. We were then generously treated to tea by his staff, which included a two-course meal of ramen noodles, omlettes and toast. Afterward, Garry took photos of every outhouse tent he could, as well as porters carrying blue-barrel waste.

From EBC, we began the long trek down to Pheriche. The trek was fariyl quick, as it was nearly entirely all downhill. However, there were some difficult passages with long, steep steps, and somewhere between Gorak Shep and Lobuche Garry's 20-year-old boot soles gave out. After some quick tea in Dughla, we found ourselves in a dense snowstorm that included some motivating thunderbolts. By the time we arrived at our teahouse in Pheriche (The "Edelwiesse"), there were 2" of snow on the ground.

Solar power system in Khumbu valley. Solar power system in Khumbu valley.

Monday, May 16

Garry, Brenda and I began our second day in Gorak Shep by climbing the famed Kala Pattar "hill" that peaks at 18,200ft and has fantastic panoramic views of the surrounding mountains and lakes and has one of the best views of Mt. Everest, which interestingly is hidden from view during almost the entire EBC Trek. The climb was harder than advertised, but the views were as good as advertized, thanks to perfect weather.

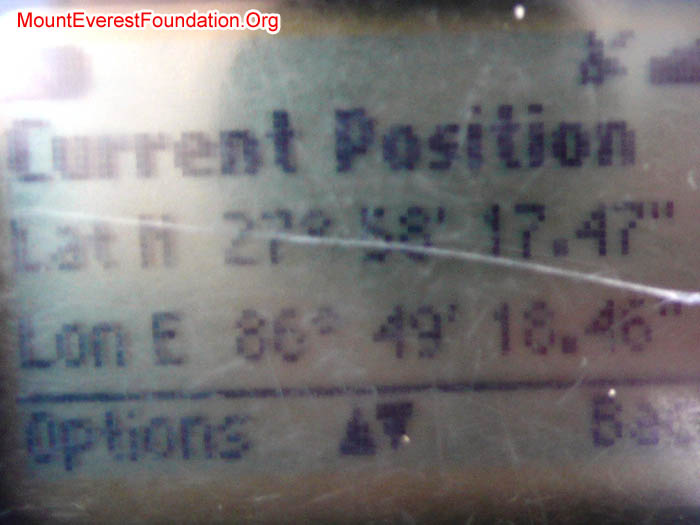

Garry, Mingma and I then met for a quick brunch after getting back to the teahouse and we went out to the site and organized some teahouse helpers who began to dig a 5-ft pit below for our percolation tests. As the local guys dug (Garry and I tried for a few minutes - there were a lot of rocks), we took our surveying equipment up and took down the relative elevations of our 2-meter grid, which we will later use to create an accurate contour map. It turned out that the labor was donated by the Teahouse owners of Gorak Shep - a nice little initial investment into the project. After the pit was dug, we did some preliminary charging of the hole for our perc tests.

In the afternoon we had a meeting with the owners of the four teahouses in Gorak Shep. Like in our previous meetings we explained the project, why we are working on it, and why we think it will technically work. Overall the owners were all very appreciative and only had positive feedback. They had a few suggestions for getting the shelter more sun exposure, including turning it to the southeast instead of southwest, and also incorporating skylights. They indicated that there are people in town who would be willing to operate the digester year-round and they offered any help they could.

Perhaps the best feedback from our meeting was a field trip with the owners to the site to look at the outline we laid the day before. Other than the suggestion about turning the building more to the east, they approved the site and the way the building would fit in with the existing ones.

After our meetings, Garry and I were invited to tea at one of the teahouses by the owner, Mr. Pemba. We spoke with his son about the project, and eventurally Garry was talking about the project to a handful of people who would later show other international visitors the idea (more on this later).

Finally, after tea, Mingma, Garry and I went out to our fresh pit and ran the percolation tests as best we could with the equipment we had (Mingma ran water in jugs for each interval from the town water source). We took down the raw data and hopefully it will be enough information for Trae to work with. Everyone we talk to is up on the idea of a vegetated field/pen thatmight absorb the effluent more safely and more productively than just putting it into a drain field.

Spring Bird. Spring Flower on the way to Everest Basecamp.

Sunday, May 15

Today was one of our most active days so far. We had an early breakfast at our lodge at Lobuche (we still couldn't figure out how they could ruin oatmeal, but it was the least satisfying breakfast of the trip to match out previous dinner). We then trekked toward Gorak Shep, taking a detour to the famous Italian Pyramid, a climate and geological research facility not far off the path.

Mingma had an "in" at the Pyramid, as he used to be a manager there. The current director was generous to show us around the 25-year-old facility which is essentially a glass pyramid covered in solar PV panels sitting on a traditional stone plynth where the researchers live. They take temperature, wind, insolation, ground temperature, etc, from points around Everest, as well as from seismic sensors. Although some of their data would undoubtably be useful to our project, they only give it out if we ask and get approval from their central office in Bergamo, Italy. Gary was particularly interested in the fact that they had a total of 43kW in solar PVs on the building and off to the side. All panels either pointed east or south, contradicting other information we were given suggesting we orient our panels to the south and west.

After tea at the Pyramid, we moved further up toward Gorak Shep (17,100ft) with another detour to check out the current active dumping pits the blue-barrel porters usewhen coming from Base camp. The pits were fairly small and unassuming at first, but as we got closer, the smell and the breadth of the dump was apparent. There were four pits, several already closed up. More concerning was that the dump site was right alongside an outlet for an adjacent glacier. Mingma confirmed that in the monsoon season, water flows freely along this bed.

After a couple more climbs and a glacier crossing, we finally arrived in Gorak Shep, which may have the highest hotels in the world. Our teahouse was so new it could only be described as incomplete. There was furniture and building materials scattered around the building and the dining area hadn't been furnished. However, they had double-paned windows in place (albeit with small holes in the frames that let in a draft) and our rooms were furnished with beds if not totally painted. Mingma explained that this was one of the nicer accomodations in Gorak Shep, and it was clear that with average food it definitely beat our lodging last night.

After lunch and a quick nap, we went out to our proposed site at the western foot of Kala Patar and discussed how well it would work. Nate Janega had already scouted out the site with Mingma, but hadn't confirmed it had good winter sun exposure. There is a large hill to the south and west of the site that looked like it would likely cut off the afternoon winter sun exposure, possibly the most important time to absorb passive solar energy. We checked out a few sites higher up and further from town, but these were very rocky. Finally, we ended up jury-rigging my sight level with a bubble level app on my android phone to determine that the ridge at the original site would work just fine and we'd only lose some late afternoon winter sun.

Having agreed on the location for sun exposure, slope, and lack of huge, obvious boulders, we set out to outline the footprint with some colored construction line. We used rocks as corner pins and squared the foundation footprint diagonally. At this point the sun had come out again, so we prepared the site for a simple contour survey by laying out a 2-meter grid, marking each point with a stone set into the ground. The site is tricky, as it drops off for a couple of meters on three sides of the building, so it's not entirely clear how the drainfield would be situated. However, the site of the building itself is much flatter than anticipated. Tomorrow we will use our hand surveying materials to measure the relative heights of the points of the grid to develop some fairly accurate contours to work with.

Taking sample for Everest bio gas project. Team enjoying.

Saturday, May 14

We left Dingboche with absolutely perfect weather. For the first time we had panoramic views of the surrounding mountains. Mts. Nuptse, Lhotse, Lhotse Shar, Ama Dablam, Pumori, Cho Oyu were seen with wonderful clarity. For the first two hours, our trek was a fantastic frolic over a slightly ascending rocky meadow. We even saw a far-off avalance on a nearby mountain. We then crossed a small river, stopped for a late afternoon tea, and then began an intense climb of 1000ft, making it up to Lobuche at 16,000ft. Along the way we befriended two stray dogs who climbed with us and saw a Lama Gerrer (Nepali Griffen).

Lobuche is not known for the quality of its lodging or its water quality, as anyone who has read Into Thin Air may remember. Everyone agreed that the food was by far the worst we have had in Nepal - the tomato soup was described as "hot water with ketchup" - but at least we only have one night here. (The business model for all the teahouses in the Khumbu region is similar to the Gillette razor model - the rooms are generally $2-5, but the food is always between $4-9 per person per meal. If you don't eat at your teahouse, your room rate may triple, and the teahouses make extra on $5 showers, $3 battery charging, $2-3 liters of water, and $3-5 wifi. You can therefore easily spend $40 or so per night).

Clouds rolled in as we arrived in town, but I went for a short climb up to the top off a nearby ridge for views of the Khumbu Glacier and a little bit of extra elevation. Now that we are so high, we are all hyper-aware of acclimitizing safetly, as we have a lot of work to do at Gorak Shep, beginning tomorrow.

Team in Khumbu Valley in beautiful day. Team planning for Everest Cleanup project.

Friday, May 13

Today is a "rest" day in Dingboche, but Mingma had set up a meeting with the local Buffer Zone Committee and other local leaders. This included the head of the Khumbu Alpine Conservatinon Council and the owner of one of the oldest teahouses in Gorak Shep. Five officials all joined us in our dining room for tea and Mingma led a similar presentation to the one we did in Namche. The biggest difference was that he translated every exchange, though most of the officials understood some english, especially with the visual materials I provided for them.

Present at the meeting were:

Mingma Sherpa, MEBP

Garry Porter, MEBP

Joe Swain, MEBP

Brenda Bednar, MEBP

Lopsang Sherpa, Head of BZC, Ward 7 - Sagaramatha

Kusang Sherpa, Treasurer of BZC, Ward 7

Ram B. Tamang, Commitee of BZC, Ward 7

Mingma Sherpa, Khumbu Alpine Preservation Council

Ang Chhiring Sherpa, Gorak Shep Teahouse Assoc. Member

Feedback was almost entirely positive, even somewhat grateful for our work on the project. Both the teahouse owner and the local BZC head offered whatever help they could, including having local residents move rocks during construction. One bit of feedback that came up more than once was the usefulness of the digester effluent as a ferltilizer for plants. Apparently the growing tourist scene has displaced more and more grazing animals, meaning there's less dung for crops. Everyone was interested in either collecting the effluent or allowing it to go into a controlled growing pen (perhaps a greenhouse?) so they could put it good use. During our trekking, we had discussed this possibility, especially because we are unsure of the drainfield requirements at this point. Removing the effluent could make the digester useful to yet another local group, which could help in its long-tern sustainability. However, we left them with the opinion that until we could test the effluent, it should only be used to fertilize grasses and other crops for animals. Mr. Chhiring said that he would still prefer the effluent as fertilizer as compared to the chemical fertilizer they often have to carry up the mountain.

Nr Chhiring was helpful in his feedback for other design ideas. He agreed that our proposed site would be a good one because of the all-day sun exposure. He didn't have any objections to siting the building at the foot of Kala Pattar. After he offered the help of the tea houses, I also brought up the idea of using shredded paper and plastic trash from the trekkers and climbers as cellulose insulation. He said that could be possible; in fact, the floor of a new part of his tea house sits above empty mineral water bottles packed under the floor. I assume this is for insulation.

There was also a discussion about the methane produced. The officials acknowledged that it may or may not produce a marketable about of gas, but they were particularly positive on the fact that the waste would be treated either way. This was clearly a priority for them. One official mentioned that he went down to one of the waste pit dump sites and noticed that the waste was not breaking down noticeably at all due to the cold and dry conditions.

The rest of the day was spent resting and checking out the local bakeries, all of which have various pies and cookies. In the morning, Garry and Brenda had gone on a short hike up to 15,000ft for acclimitization while I tried to sleep off my cold. After a strong americano at a nearby "french" bakery, I did the same hike in the fog that had rolled in. For the first time on the trek, the effects of the altitude became apparent, as my legs felt heavier the higher I climbed.

Tomorrow we trek up to Lobuche, just a short stop before Gorak Shep.

Worker digging soil for Everest Cleanup project. Tribute to climber

Thursday, May 12

Today was arelatively short day of trekking to move further up the valley. As we moved out of Pangboche, we got our first glimpse of Everest, but it lasted no more than a minute, as clouds appear instantaneously out nothing with the blink of an eye. The walk was relatively easy compared to previous days of trekking, particularly for Brenda, who didn't realize a 15lb rock had somehow appeared in her pack for the last climb. After a clear but windy three-ish hour walk back down to the river and up another bluff, we ended at Dingboche (14,200ft) in time for lunch. Not an hour too soon, as clouds began to blow in, and visibility (and sunlight) became nonexistent.

The afternoon became a rest day. I had developed a minor cold the day before, and took a nap to try to nip it. I realized the cold, dry air at this elevation will turn a common sore throat into a virtual inability to speak. We met for a brief dinner in the teahouse dining room, which was probably the warmest space we've encountered since our stopover in Dubai. Unfortunately, this was because of a stove in the middle of the room fueled by dried yak dung, so we had to repeatedly dodge outside for fresh air.

Team reach Everest Basecamp. Team working at Gorek Shep Everest Cleanup project.

Wednesday, May 11

Today is a trekking day from Namche Bazaar to Pangboche (12,800ft), via Tengboche and Deboche, the locations of the oldest monastery and nunnery in the region, respectively. We left after breakfast and climbed out of the Namche bowl and traversed the flanks of the river, only to descend almost 1000ft down to the river to cross it. After lunch we climbed straight out of the valley to Tengboche (12,700 ft), where Garry visited a memorial for a friend's father who had been on the first American team to summit Everest.

We then trekked about 30 minutes down to Deboche, where we visited the nunnery there. AWB-Seattle has been working to design a couple of buildings on this site for the nuns, including a new meditation center. Laura Rose, the project lead, had given me some documents for the nuns and a list of photos she needed. We found the nuns chanting in the middle of a 12-day silent meditation, so we left the documents with them without speaking to them. We then had some tea in the kitchen, where Mingma caught up on the news there (he has been very involved in the development of the nunnery projects for a long time).

After visiting Deboche, we again trekked down to the river (Gary always says never cede your elevation, but sometimes you have no choice), and trekked up to Pangboche. Garry had requested we stay at the teahouse of an old climbing friend, so we stayed at the Highland Sherpa Resort, which served some good Sherpa stew.

Tuesday, May 10

A blur of action in contrast to yesterday's relatively quiet rest day. After breakfast I ran down to print some last-minute energy-modeling documents that had some good graphics to help explain things at our meeting with SPCC and the Buffer Zone Committee. Mingma met us at 9am to go over how the meeting would run and then we walked over to the SPCC headquarters, which were on the second floor of a surprisingly unassuming building.

Mingma moderated the meeting after introductions. He had Garry give a rousing history of the biogas project and why it meant so much to him. Garry had rehearsed his points beforehand and nailed his recounting of his personal experience on Everest, including how he hated leaving his waste on the mountain as he descended for the last time. He also talked of Dan and Mingma's long involvement in the project.

After Garry set up the background, I presented the new developments in the technical design for both the digester and the shelter. Back in Seattle I had put together packets with plans, sections, site information and other visual information for these meetings, and they came in handy in communicating with three officials with varying levels of English. I also presented a full updated set of plans, which included engineering. The SPCC had sent us a list of technical questions, including how to store the waste throughout the year and how to keep the digester at the operating temperature.

A discussion followed, more led by the president of the SPCC, Ang Dorjee Sherpa, and Mingma. After asserting his doubts about the technical feasibiilty of the project, Mr. Dorjee became more optimistic, eventually saying "We must try it. If we don't try, we won't know if it won't work." From this, we began discussing the administrative hurdles in front of the project, including permits from the Sagaramatha National Park.

It soon became clear that the most straightforward path with the least red tape would be partnering with the SPCC and the BZC, since each has control over certain aspects of the park. This would allow us to bypass most of the normal National Park permit requirements, including the dreaded Environmental Impact Assessment. Like in the US, this could take up to two years and require several studies that could be expensive because of the remote location.

The final agreement of a partnership, to be confirmed with a signed MOU between all parties is as follows:

The SPCC will own and operate the project. It will share oversight in the permitting and construction ofthe project.

The MEBP will provide the initial capital investment, technical design, and long-term technical support.

The BZC will facilitate approvals and provide legal support and the acquiring of the land in the National Park.

This partnership was exactly the outcome we had hoped for (and absolutely needed). Even more exciting is that both parties appeared to accept our technical design wholesale. I asked what information they would need (plans, modeling, etc), and they said nothing else would be necessary to move approvals through.

We agreed to type up the meeting minutes and an MOU defining the partnership. We would leave these documents with the SPCC and the BZC and all parties would sign them when we come back through Namche Bazaar next week.

After the meeting, all four of us were excited, but had a lot of work to do before the end of the day as we needed to get the documents to the other parties. Brenda wrote up the meeting minutes, and I drew up a draft MOU, which was proofread by all the team members before I formatted the documents and had them printed. (For future reference, it costs 50 cents to print a black and white page in Namche Bazaar, so any heavy printing needs would be best taken care of in Kathmandu.)

After dinner, we packed up as much as we could, as we had a very long day of trekking ahead of us. On group work, Mingma's Sherpa wisdom of the day: "A thousand hands is golden; a thousand mouths is poison."

Monday, May 9

Today is a working/rest day in Namche Bazaar. We got word from Mingma that the SPCC head arrived in town this morning, so we are on for a joint BZC/SPCC meeting tomorrow morning. Therefore Mingma took the day off and Garry, Brenda and I set out on a four-hour day hike up to the towns of Khunde and Khumjung (12,600ft) to help with acclimatization. There are supposed to be fantastic views of some of the more prominent mountains in the area, including Everest, but after an hour of clear weather, clouds rolled in and we ended up getting rained on on the way down to Namche.

Garry and I attempted to visit the pre-fabricated REI-funded Emergency Disaster Center on the way back, but found it located on a small military base. The guard let us into a small dark office so we could as permission (he didn't speak any English) to check out the building, but no one came to meet us, and after 10 minutes we left. We did notice the outside of the building looked weathered and appeared to be peeling, which struck us as odd for a weeks-old building. It's possible it hasn't been finished yet, though the photos in the news articles made it look much better. We decided to ask Mingma if he thought it worth pushing the guards at the base to get a closer look.

The rest of the day was spent recovering from the hike, which included my first shower since Friday, and finishing preparations for tomorrow's meeting by printing out some last-minute documents at a local internet cafe.

Photo Joe

Sunday, May 8

We trekked a challenging morning from Monjo to Namche Bazaar (11,000ft), with a net gain of about 2000ft, but considerably more overall climbing. The trail criss-crossed the river fed by the Khumbu Glacier (and contaminated by any waste that is currently dumped below Gorak Shep) before moving off the banks to Namche. We made didn't have much of a problem despite the elevation, though we made sure to take plenty of breaks. Mingma's Sherpa wisdom of the day: "For a long life, do not take short cuts."

We made it to the Yak Hotel, owned by friends of Mingma's in time for a late lunch. Mingma is from Namche Bazaar and of course knows everyone we pass on the street.

Although most people spend two nights here to acclimatize, we have scheduled three to make it easier to schedule meetings with the Central Buffer Zone Committee and SPCC. Namche is the center of the Sherpa region, and it is home to both of these organizations. I'd also like to meet with a builder or two here, as well as check out the Emergency Center just built this year with heavy support from REI.

After a nap we reconvened to plan for our upcoming meetings over coffee and surprisingly decent apple pie. Bakeries are on every corner here and most now serve Italian espresso drinks - sometimes you wonder if this town would exist if there weren't hundreds of western tourists coming through every day. In the meantime, Brenda set up a Facebook page for the MEBP to which we can hopefully post these notes and some photos.

Mingma explained the dynamics of the BZC and the SPCC, and how we might present the project to both of them. We have brought packets of visuals of the project, as well as a full plan set. The SPCC will be most interested in our progress solving the technical aspects of running a biodigester at high elevation. We discussed how to address the "exit strategy" question and how we envision these organizations sustaining the project after it's built. Mingma suggested we ask them for their suggestions, as they already have mechanisms for extracting fees, taxes and paying for infrastructural and environmental resources.

Mingma was confident that our showing our faces in the Khumbu Valley alone would go far in showing how serious the team is about implementing the biogas project. Nevertheless, he recommended Garry begin by recounting the history of the project and why everyone involved is so invested in the idea, the people and the region. The head of SPCC is supposed to arrive in Namche from Kathmandu tomorrow, so Mingma hopes to schedule the meething for Tuesday morning. The BZC meeting may be at the same time, or possibly on Monday.

Photo Joe

Saturday, May 7

We met Mingma at the airport early to catch the first flight to Lukla (9000ft), the beginning of our trek. A series of miscommunications at the airport lead to our seats being given to other travelers. However, Mingma found us an alternative almost immediately. A helicopter (piloted by a 42-year-old journeyman named Ryan) was going out to Lukla to pick up someone with a broken leg, so we caught a 45-minute flight that spared us from having to land on the infamous 18-degree landing strip.

After reorganizing our bags and distributing some weight to two porters, the four of us trekked down to Phakding (8300ft) where we had lunch. This is the traditional first night on the EBC trek, but it was only 1pm and we were feeling energetic, so we pushed on to Monjo (9000ft) to save ourselves some climbing the next day to Namche Bazaar, probably the hardest day of trekking.

On the way we documented some tea houses under construction and the building methods they were using. There was a lot of wood framing, but some hand-carved stone blocks as well. One cladding material I hadn't seen in photos before was very thin (.45mm) sheet metal. It was flat and nailed directly to the studs, which were about 32" on center. The only other layer in the wall system was a sheet of 5-10mm plywood on the inside, which also could be the finish. There was significant oil canning on the metal sheets, which come in rolls. However, it's definitely cheaper than stone or wood.

We passed a friend of Mingma's on our way up to Monjo who was an 85-year-old Coloradan who had become a Buddhist monk years ago. We told him our destination and his response was, "You're going to Base Camp? You should save yourself some time and instead check out the New York or Seattle Dump."

Friday, May 6

Today was our only real day in Kathmandu before our trek, so we spent the first part of the day chasing down shopping list items, including medication for altitude sickness, trekking equipment, a map, and a SIM card for an emergency phone (+977 9823439534; Garry's is 9823439600). Mingma Sherpa, our project Sherpa liason and designated guide for our trek up the valley, met us after breakfast to take us around Thamel and and talk logistics. We later split so he could aquire our trekking permits. Our afternoon was spent figuring out how to re-pack our bags, send text messages, catch up on sleep lost to jet lag, and getting our gadgets charged (a challenge given the rolling blackouts schedulled everyday by the city).

Thursday, May 5

Garry, Brenda and I arrived in Kathmandu around 11pm after a delayed connection from Dubai. We were able to check out downtown Dubai and the Burj Khalifa thanks to a 6-hour layover and a generous immigration official. We ate a Lebanese & Armenian meal in the upscale mall overlooking the central canal, which was lucky because the flight to Kathmandu was a spartan flight mostly for migrant workers that offered no food or drinks. Our hotel was moved at the last minute due to overbooking, but this wasn't a problem for us. We ended up at Hotel Mums House south of Thamel.

Photo Joe

=======================================================================

Update on Mount Everest Biogas Research Project

CLEANING UP MT. EVEREST (Converting poop to power)

For climbers all over the world, summiting Mount Everest represents a lifetime dream and one of their greatest achievements. But when they leave Mt. Everest, their human waste is left at the nearby Sherpa village of Gorak Shep. Today’s average climbing season produces nearly 12,000 kg of solid human waste. While recycling and trash programs are now in place, no real solution exists for the human waste generated by the climbing community. Modern treatment plants are impractical to build and maintain in this isolated corner of the world, so this waste is currently dumped into unlined pits at Gorak Shep, contributing to an increasingly polluted water supply. Despite all the efforts to clean up Mt. Everest, it is this environmental disaster that we are addressing, and we need help to get there!

In April 2010, a group of volunteer engineers and architects from the Seattle area formed the non-profit Mt. Everest Biogas Project to address this environmental issue. We have designed a biogas system that will safely break down the human waste and create clean burning methane gas for the Sherpa community. Our design includes not only the biogas digester, but also a small shelter to minimize temperature variations. This is a familiar technology; biogas digesters are used prolifically throughout Nepal, India and China.

Porters carrying blue barrel toilet drums at Gorak Shep.The famous Hillary Step going up towards the summit of Everest (Richard Pattison Photo).

Our design has been peer reviewed by local technical professionals and now it’s time to implement it. The biogas system concept was presented to Nepalese officials and teahouse owners in 2014. Now that the design is nearing completion, it is time to give them an update and begin planning to break ground.